It was the first summer that I was here in Ashland, when I still enjoyed an innocent and unbounded hope about the future, which has given way to a far more pragmatic sense of qualified optimism. I was taking math classes at SOU, my son was not yet born, and I took a certain joy in doing my calculus homework in the evening, after my wife and infant daughter were already sleeping, at the few late-night haunts in town with a decent kitchen staff and after-hours menu.

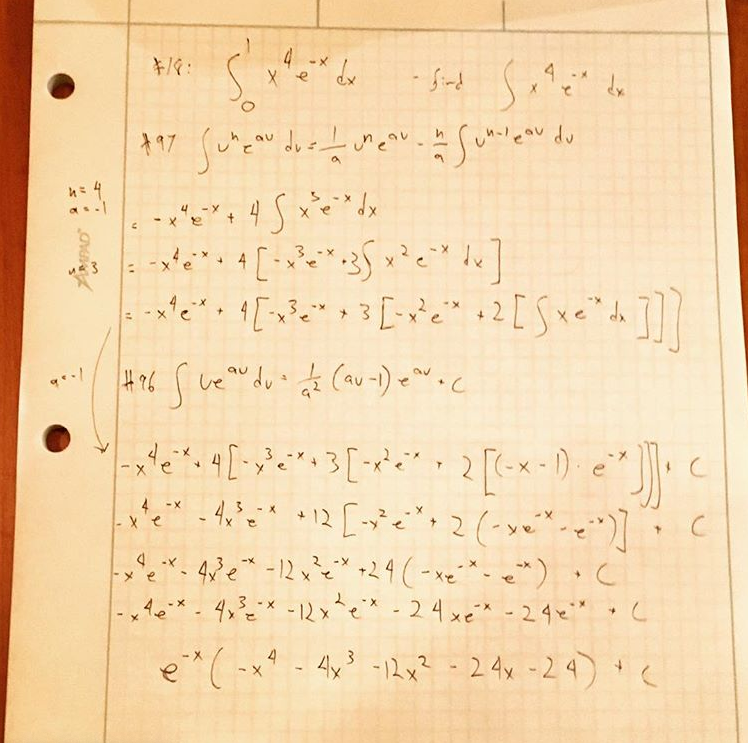

That night, I was at Harvey's with a cheeseburger and fries, nursing a cider, and working out integrals per a worksheet of common transformations, in longhand on graph paper. I happened to overhear an exchange between the bartender and a slightly-drunk, eager beer-drinker who had just arrived from a show that had just finished down the street at Standing Stone Brewery.

Bartender: What can I get you?

Customer: I'll have a tap beer, whatever you got in an IPA.

Bartender: Sure thing. Where ya comin' from?

Customer: I just saw the Brothers Reed over at Standing Stone. They just finished up.

Bartender: Cool, you know, I've heard about those guys but I've never seen them play. How was the show?

Customer: [Blank stare]. They're very popular.

I met a retired professor from Berkley at a holiday party earlier this month. It came up in our conversation that he hastened his retirement (only slightly, he was quick to clarify) in part because his students would no longer visit him during his office hours; instead, they sent him text messages, wondering how soon he would be able to post a PDF of the minutes from his latest lecture to the class forum on the university intranet. Human interaction has quickly become a side-product, a hassle, a sort of if-I-must technicality of last resort. He felt less connected to his students quite generally, and also felt the pressure to make way for faculty that had more facility with that stuff: presumably email, and text messages, and online form-filling. He mentioned as well that working out grades at the end of the semester seemed to be decidedly more error-prone, now that he was forced to fill out a spreadsheet online, instead of using the now-archaic combination of ink and paper.

That yearning for a curated experience has spilled over into music for the younger generations, it would seem - as if the music fans of today are only interested in perusing the top 10 list for their genre of choice, with little regard for how it is assembled, or what the criteria are for excellence. Perhaps, a kitschy twist on the line from Arnaud Amalric, and the disastrous Albigensian Crusade: "...the Lord knows who are His." As long as someone is sorting something out, little matter the details.

Just tell me what is popular, so I don't have to waste time figuring it out for myself.

Where's the fun in that?

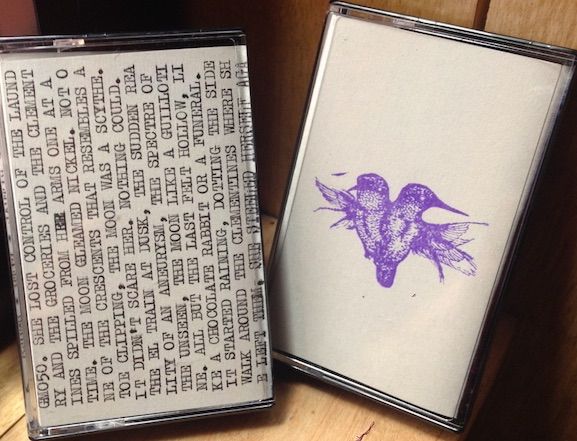

There was once a time, that I remember fondly - if, to be fair, with some embellishment - that personal tastemakers ran amuck in society, doing very tedious things to make their preferences known. Things like designing their own band t-shirts with markers and ball-point pen, making garish tie-dyes in plastic buckets, and spending long hours making cassette tapes from radio broadcasts for sharing with friends, or prospective lovers. The mix-tape has resurfaced of late, but it no longer represents what it once did - the mark of a tireless commitment to personal branding is now gone, such that we can simply enter a phrase into a search box, click a bunch of '+' symbols, and share to socials without so much as having to press play and record at the same time on a cassette deck somewhere. At the risk of sounding like an old man waving his fist at a windmill, I would just like to make the point that in those days it seemed both plausible and logical, perhaps even inevitable, to have differences of opinion - and by extension, many if not all of us were forced to contend with the ambiguous details of our own taste. Today, not so much. Even with a few beers in his system, even when speaking to a friendly and attractive bartender with genuine curiosity about the music he just saw, the average concert-goer can only muster up a fuzzy reference to collective opinion, and a slight sense of horror at being asked to form an opinion on the fly.

It is possible that from the quaint confines of our Rogue Valley, the great patterns of humanity are too far in focus to yield any empirical verity. Yet, it is also possible that we have lost sight of a simple truth: that personal conviction is sexy, and blind allegiance to the perceived zeitgeist is not; and that unless we make time and space in our society for the individual's need to turn inwards and explore, only vague intimations about collective opinion will remain in place of the once-passionate embrace of unique preference.

With that, I yield the remainder of my time to the youngster who speaks, without irony, for an entire generation.