That Was a Long Time Ago

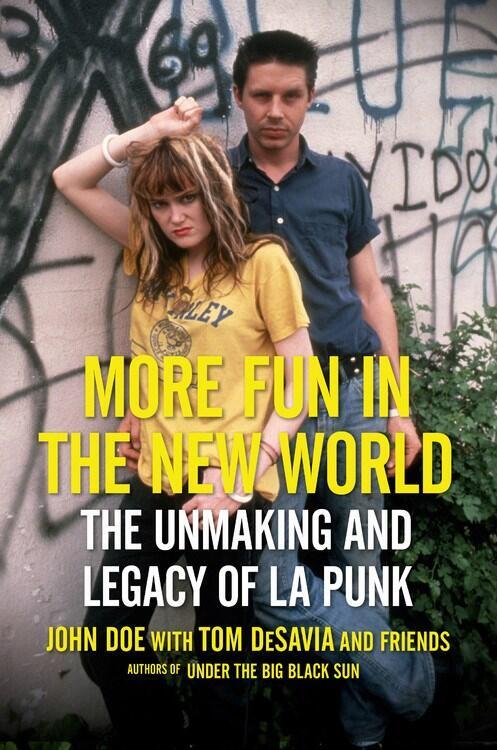

I was just reminiscing about my time in Los Angeles, and even the early days of writing for CHILLFILTR, and I thought about being approached by Hachette Books in 2019 to help promote the hardcover edition of More Fun in the New World: The Unmaking and Legacy of L.A. Punk. It's a fantastic book, and I was happy to promote it. But the twist is that Tom DeSavia (the Grammy-winning co-author) and I have a bit of history together.

I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to continue evolving as a creator, outside of any large external pressures to succeed financially, for more than 2 decades now. My success as a software engineer has kept food on the table, along with the talents of my amazing wife, so that a decades-long career in music that never turned a profit has not been as much of a burden as it could have been. Even so, I was forced years ago to come to personal terms with the disparity between a success that I felt like I deserved, and the opportunities that actually did happen to fall on my plate. Of course, I made plenty of my own mistakes. But still.

I have moments where I feel guilty for disappointing my younger self: where I wish I could just go back and be smarter, and more engaged, and less drunk, for example. But that was a long time ago. All I can do now is tell the story.

I was working with fellow musicians Angel Roche Jr and Dave Lichens, and UK guitarist Richard Corden, in a band called Revolver (not to be confused with this band), and we were getting pitched to the majors by our friend (at the time working for EMI) named Matt Messer. We got flown to NYC to have a talk with Elektra, I remember, and they picked us up in a limo at the airport. I would say the time frame was late summer, 2002.

We were attempting to latch on to the British rock invasion, in a sense, as an American counterpoint to bands like The Verve, Catherine Wheel, or even Oasis. We got close, but never actually signed a deal, and there are many stories about what happened there that I won't get into.

What I want to talk about is what happened after we got back. It's just a short anecdote, but it still makes me smile.

It takes a while to get a record deal. Every day that goes by you wonder a little bit, and you constantly have to remind yourself to just stay calm and let the process play out.

We were only in New York for a few days, and then we were back in Los Angeles, waiting around for an affirmation that never came. We did the requisite preview show at SIR Hollywood for 'label reps only,' Rick Ruben was there, things were looking good.

I don't remember exactly what capacity Tom DeSavia was in at the time. I know he's done a lot of work for ASCAP, and now he works in publishing, but I could swear that he was doing A&R for Elektra. We were all at his house in the Hollywood Hills, which I think he had recently moved into, and he was excited about his cd collection. He felt like he had been able to collect pretty much everything worth listening to from the last few decades.

So he looks at us—Angel, Dave, Richard, and me—and he says:

Name any song, by any artist, and I'll bet you I can find it in my cd collection.

I don't remember anyone else even giving it a shot. But for some reason, I immediately said: "Birds of Fire" by Mahavishnu Orchestra. I have always had a strained relationship with progressive rock and jazz fusion, I never quite connected with Yes, and Rush, but to the extent that prog-rock ever appealed to me, my love for it was on the jazz side for sure. I was always more Miles Davis than Phish, for example, which made the detox from my earlier days as a Deadhead particularly painful. But John McLaughlin was always a hero of mine, and for some reason that was the album that came to mind. We didn't bet, although I'm sure if I'd had a 20 dollar bill in my pocket I could have doubled it that day.

So Tom ran around, briefly, the big living room he had with wall-to-wall shelves built in to house his massive cd collection, looking for a match, but rather quickly came back and, slightly sheepishly, admitted that "Birds of Fire" was not in his collection. And that was that.

From what I heard, at some point later Tom was the victim of a home robbery, and one of the things that never came back was his massive cd collection. It's hard to imagine now, but in those years, Spotify wasn't a thing yet, and the relatively new concept of cds—and digital music in general—had manufacturers marketing the cd format very effectively to collectors, in a way that might feel similar to the recent energy around vinyl.

What I find sort of quaint about this memory is the idea that someone could even conceive of owning every piece of music that 'mattered.' This was a sentiment I remember from those pre-streaming years, where there were people like Tom DeSavia—an ex-girlfriend of mine used to speak similarly about her own taste in music—that still felt like they had a handle on everything that was worthy of attention. I would hope that now, we can all agree, that the entire spectrum of music that can be considered noteworthy lies beyond the grasp of any one mind, or platform. This speaks to another of the conversations I like to have with myself, about the importance of indie art's "long tail." I strongly believe that society needs to come to terms with this. Simply put, we need to ask ourselves: is short-term success, as measured by individual engagement, an adequate proxy for long-term value?

And I would say, unequivocally, no—there needs to be other mechanisms in place that support the complicated idea of non-commercial curation, where we attempt to create a blueprint for what deserves to be noticed that can exist outside the nebulous and fickle confines of popular opinion, and the deeply flawed ways that we measure such a thing. Because if the last few years can tell us anything about the future, it is certainly that concepts like popular consensus and public sentiment will continue to become more, not less, obfuscated by the very tools meant to measure them. The entire Spotify ecosystem, for example, is rife with bots and paid listens. So the question becomes, whose ears should matter more?

And beyond that, market dynamics are not sufficient to support a cultural cornerstone like the arts. When the pandemic is over, and live performances come back in earnest, the world will be shocked by how many musical venues were lost, and how many musicians were forced out of the industry. It's a fragile balance in the best of times for the vast majority of musicians. We need to do better.

In terms of the record labels, and the failures of 'cigar-chomping' executives, this is something Frank Zappa discussed, years ago (linked here). The gist of it is that we decided, somewhere in the transition from the 70's to the 80's, that instead of putting out a bunch of music, and seeing what sticks, that record labels could appoint 'arbiters' of cool, and decide before the fact what was worthy of label support. Which is fine, and frankly that was exactly the role that people like Tom DeSavia and Matt Messer were playing. This was something they were both exceptionally good at.

But here's the twist—back then, there was still an important concept around discovery, and about uncovering something totally fresh. That was the holy grail, the idea of finding something truly amazing and bringing it to the world. That is the thing that we have lost, in my opinion. Because the advice you get now, as a songwriter and performer, is to just succeed—to connect with fans, to tour incessantly, to self-produce, and to demonstrate the 'economic viability' of your project—and once that is done, judging on the merits of that process, you may enjoy some support from labels. Maybe.

So labels are now in a position to only bet on bands that are already winning; and on a certain level, it is hard to blame them. And, to be fair, there are labels like Nettwerk (my very favorite) that still do, in my opinion, something akin to discovery.

But if you had asked David Foster Wallace about the transition of mainstream art from the 90's into the new century, he would have probably mentioned something about how American 'exceptionalism' segued into cynicism. This is now something that is hard to argue with: the very concept of cynicism, along with the idea of being woke, has been co-opted by an increasingly consolidated media landscape in order to sell us back our own status quo. It's the best we can do, they always say.

But that is the thing that I've learned from a life of making mistakes: you can always do better. We need to do better.

Adam Levine said recently that there aren't any bands anymore. His fans quickly remarked that he, in fact, is in a band. But that wasn't exactly the point, in my opinion. I feel it too—as much great music as there is being made right now, some of it feels forced. Sure, there's a lot diversity right now in the genres of hip hop and electronic, as well as roots and country, but in terms of rock, and pop, the flame feels pretty low.

Maybe that's what he meant. These are the top 10 artists of 2020:

- Post Malone

- The Weeknd

- Roddy Ricch

- DaBaby

- Drake

- Juice WRLD

- Lil Baby

- Harry Styles

- Taylor Swift

- Pop Smoke

I don't see any bands on that list. If you follow the chart, you have to get to #55 just to find the first band. Wanna guess which band it is?

Queen.

Maybe Adam Levine is right.

That's the thing that makes me kind of sad, is that there were just bands. There's no bands anymore, and I feel like they're a dying breed. — Adam Levine

TL;DR: Mahavishnu Orchestra was a fine quintet from New York City, formed in 1971, that was noted for radically high volume levels, complex textures, and fast modal playing. Tom DeSavia used to have a large cd collection, but he probably listens to Spotify now.

Adam Levine says there's no bands anymore.

Ethan Hawke says that art becomes sustenance right when your father dies.